Book Review: ‘The Director,’ by Daniel Kehlmann

- Movies

- May 8, 2025

The directorby Daniel Kehlmann; Translated by Ross Benjamin

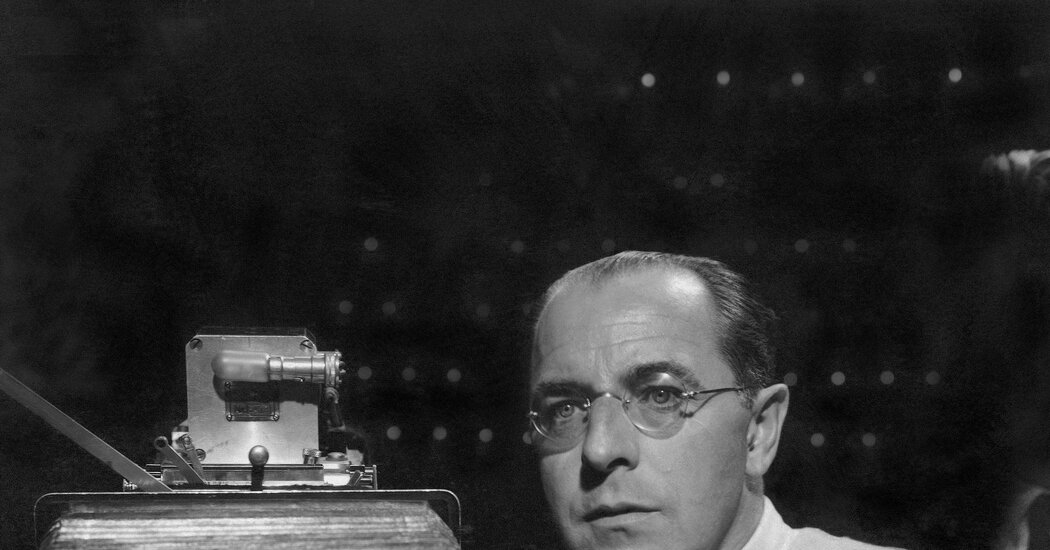

Film and Nazis stars are irresistible ingredients in any book. “The director”, Daniel Kehlmann’s new novel, elegantly entertaining about the great Austrian filmmaker GW Pabst, sacrifices both, detailing his intimate or symbiotic ties. Here, Greta Garbo and Joseph Goebbels have only two degrees of separation between them.

Pabst (1885-1967), along with Fritz Lang and FW Murnau, was one of the great three of the most cosmopolitan and politically committed trio trio. Considered a leftist, Pabst achieved a popularity for a series of very frank silent films and social sex and sex, including “secrets of a soul” (1926), which to played with Freud and “Pandora’s Box” (1929), the Eils Expervisly devasting flapper.

Red Pabst, as he was called at the beginning of his career, made a brilliant adjustment to the sound with the film against the war “Westfront 1918” (1930) and “The Threepenny Opera” (1931). But he was a bad adjustment in Hollywood, where, speaking small English, he arrived through France after the Nazis came to power. Then he returned to Austria, now part of the Reich, maybe to visit his sick mother. Trapped by the outbreak of the war, he was there, making several apolitical films of “prestige” for the Nazis and compromising his reputation forever.

Pabst was “a precise and demanding artist”, according to the scholar of cinema Eric Renschler, as well as “an extremely private person who did not easily disseminate his thoughts.” Pabst of Kehlmann is a talented psychologist when it comes to directing the actors, but a stranger for himself in all other issues, a genius who thinks of films but cannot direct the flow of his own life.

The German title of the novel, “Lichtspiel”. In fact, starting with a chapter in which Pabst’s fictional deputy director becomes a disastrous television interview to remember his former boss, Nightmare’s novel Carans from Nightmare. Some, like the starter, are absurd. Others, such as Pabst’s complete disability to navigate at a Hollywood party, are the painful comic. Others, once Pabst and his family return to Reich, are scary.

Was Pabst an opportunist, a victim of circumstances, a cowardly practitioner or mischievous obedience or simply a solipsist accommodist? Allahe will not understand Hollywood, learn the Rules of the Reich when the propaganda office was convened, directed in the novel by the unidentified “minister”. (Soft, threatening and self -safety, Goebbels easily directed the director).

In another part of the Front of Culture, Pabst’s wife, Trude, experiences the new group thought of the time when she is invited to work in a reading club directed by the Ams of High Quality House and is completely dedicated to the fiction more sale of the Nazi (real life). Pabst’s little (fictional) (fictional) (fictional), discovers his own accommodation strategies as a matter of survival in school courtyard.

In addition to inventing a chilling interview in which the minister takes with Pabst, Kehlmann imagines that the director obtains the Hollywood Ploinfoff from his own discoveries, Megastar Garbo and a founding Brooks. An even more alarm meeting with the filmmaker of actress Turner Leni Riefenstahl, who starred in the spectacular Pabst alpine “The White Hell of Pitz Palu” occurs on the set of his candidate for Opus Magnum, “Lowlands.”

Kehlmann, author of other reinvented stories such as “Measure The World” and “Tyll” (the letter also translated by Ross Benjamin), bases key real life scenes: Riefenstahl not only directed his wild project, but also danced about 15 years of chicken. Infamous, the attempt of the authenticity film involved importing more than 100 Romani adults and children from two concentration fields for use as extras (and perhaps send them to their fatality).

As the production was with projects, Reifestahl requested the help of its former director. The story of his collaboration found in his monumentally selfish memories of 1987 is happily contradictory to those of Kehlmann. Attributing the changed personality of Pabst while passing in Hollywood, Riefenstahl describes Pabst as “cold” and “despotic”, which is the way Kehlmann represents here. His Pabst is, on the contrary, confused. If the author takes some freedoms by giving life to his characters, his unpleasant portrait or riefenstahl is certainly plausible. This is also his idea that Pabst, bewitched by Brooks, wore a life torch for her. (This differs from the analysis of the “Mr. Pabst” that Brooks tested in his wonderful “Lulu in Hollywood” memories, but his acquaintance?)

In other places, Kehlmann freely adds secondary characters and carefully manipulate the chronology: for dramatic reasons, “the white hell of Pitz Palu” (1929) and the “metropolis” of Fritz Lang (1927) are almost simultaneous. But when playing with the historical record, Heygely, he manages. The novel has an academic subtext, which reviews the beloved Achant Henny Porten, here a star member of the Trude book group, and the young director Helmut Käutner, who sacrifices Kehlmann’s friendly advice. Each managed to somehow resist the regime. Porten refused to divorce her Jewish husband; Käutner flew under the radar with unpretentious humanist films, then flourished in Western post -war Germany.

The most informal, Kehlmann also spray his text with delicious hypothetical. The premiere in times of war of the 1943 film by Pabst “Paracelsus” is counted through the eyes of the British comic novelist PG Wodehouse, a prisoner (privileged) of whom, in the Kehlmann count, he is trotted by the Reich to give him. “” Riefenstahl, a guest partner, looks like “a peculiarly chilling creature” with the skin “emitted by Bakelita.” But well, and joy the movie.

A heavy medieval biographical film about a legendary Swiss doctor (played by Dr. Caligari himself, Werner Krauss), “Paracelsus” Inexplicia explodes in a dance sequence of St. Vitus by St. Vitus so strangely stylized, such as Pabst so Pabst has been as Pabst as Pabst as Pabst. “For a moment I hesitated if it was something I had really seen,” Wodehouse reflects in the novel. “Could I have dreamed?” Indeed.

“Paracelsus” allowed Pabst to direct on a scale and with a freedom could never have enjoyed in the United States. While his Hollywood experience may not have a leg as humiliating as Kehlmann achieves it, he undoubtedly hurt his vanity. Most other refugees from Jews from the German film industry who adapted for necessity (some very remarkable); Only Pabst had the option to return and entertain the possibility that he could recover his former eminence.

The hypothetical hypothetical of the novel Conerns Pabst The movie Lost “The Moland Case”, an adaptation of a Karrasch novel no less, filmed in Prague when bombs fell on Germany. Probably never completed, the film disappeared in the rubble. Therefore, Kehlmann is free to imagine it as an expressionist and anti-Nazi return to the Weimar roots of Pabst.

Pabst’s attempt to transport this alleged masterpiece back to Vienna is the culmination of a tragic slap of slap, a live instead of interns. “The director” is a wonderful performance, not only flexible, horrible and bitingly to Droll, but translates fluidly and absolutely convincing.

The director | By Daniel Kehlmann | Translated by Ross Benjamin | Summit | 333 pp. | $ 28.99