One of the Weather World’s Biggest Buzzwords Expands Its Reach

- Enviornment

- May 3, 2025

For people on the west coast, atmospheric rivers, a meteorological phenomenon that can bring heavy rains or snow from San Diego to Vancouver, are a characteristic as common from winter as the Nor’eaasters in Boston.

Like those storms on the east coast, the “atmospheric river” can feel like a fashion word: more attention grabbing than only “heavy rain”, even this is how most people who walk through the streets of San Francisco will experience it. But it is also a specific meteorological phenomenon that describes the storms rich in moisture that develop on the Pacific Ocean and volcan the precipitation when they collide with the mountainous chains of Washington, Oregon and California.

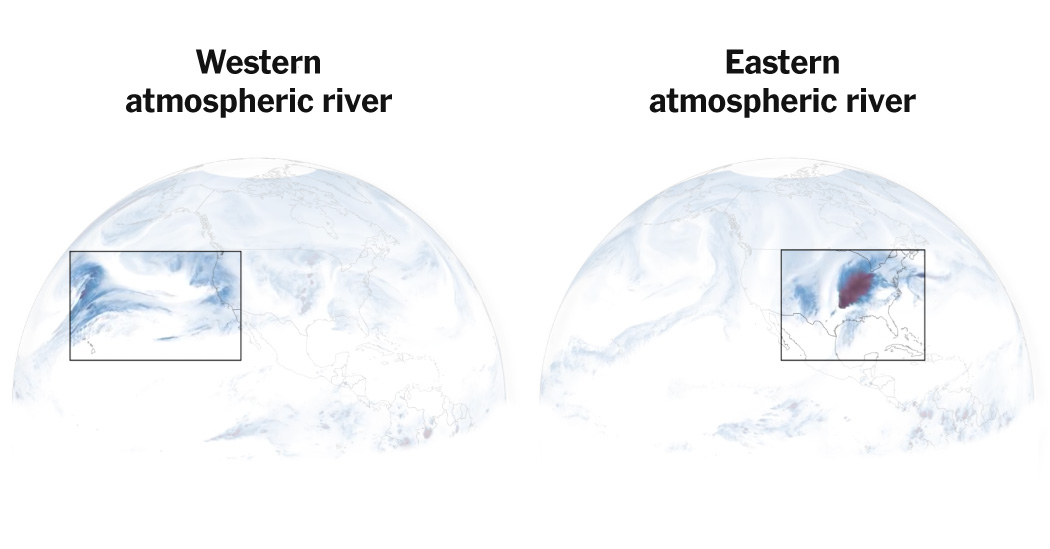

However, these exceptionally right columns transported through the atmosphere by strong winds are not exclusive to the west coast. They occur throughout the world, and a growing number of meteorologists and scientists begin to apply the term to storms east of the rocky mountains. When the days of heavy rains caught fire in the mortal floods in the center and south of the United States this spring, Accuweather set the unusual climate in an “atmospheric river”. CNN did so.

While some researchers expect to see the most widely adopted term, not all meteorologists are doing this, including those of the National Meteorological Service. In the center of the debate there is a fight on how forecasting describes the climate of the day.

Atmospheric rivers can extend up to 2,000 miles.

They are generally formed on oceans in the tropics and subtropical, where the water evaporates and accumulates in giant steam rivers in the air that move through the lower atmosphere to the north and south poles. They are clearly narrow, on average that measure 500 miles wide and extend 1,000 miles. Many Waker atmospheric rivers provide beneficial rains and snow, but the strongest can offer heavy rains that cause floods, landslides and catastrophic damage.

The rain does not fall on its own. Just as water needs to be squeezed from a sponge of law, an atmospheric river requests a mechanism, specifically, ascending vertical movement, to release rain and snow. When the atmospheric rivers push up, water vapor cools, condenses and precipitates.

On the west coast, this process occurs over and over again at the beginning of spring, and is easy to understand, since the mountainous chains such as the waterfalls and Sierra Nevada provide that elevator up. The atmospheric rivers that come from the Pacific Ocean crash against the mountains, which causes the water vapor to rise and become liquid.

It is more complicated in other parts of the country, where the upward elevator generally comes from the instability in the atmosphere that is less tangible, and less predictable, than a mountain. In the center of the United States at the beginning of April, the cold air swings from the north plowed under an atmospheric river that came out of the gulf, pushing that humid and humid air.

“Once the warm air rises to a point where it makes it warmer than its environment, it can increase the explosive, and that results in serious thunderstorms,” said Travis O’Brien, an assistant professor at the University of Indiana, who was co -author of Drew Drewtion Drewtion East Coast.

The flood was extreme in places like Kentucky, Tennessee and Arkansas, some places recorded more than 15 inches of rain, as the atmospheric rivers flowed to the region for five continuous days.

Why are they called that, anyway?

Atmospheric rivers have always existed, but scientists only beyond recognizing them in the mid -1970s and eighty with the development of geostational operational environmental satellites, known as Goes, which is the national and ATOSP by Spepasp

“Before that rained heavy on the west coast, and nobody really knew what was happening,” said Clifford Mass, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington. “Before that, we don’t talk much about that.”

Advanced satellite technology provided the images that allowed researchers and meteorologists to see atmospheric rivers. They started talking about them and appointing them.

The term Atmospheric River was first presented in the 1990s by two at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Reginald E. Newell, Meteorologist and Professor, and Yong Zhu, a research scientist. At the beginning they used the term tropospheric river, after the lowest layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, where most of the climate comes. Two years later, they had become the Atmospheric River, a description that men chose because the rivers “carry as much water as the Amazon.”

Is the term exaggerated? Sometimes.

It was not the 2010 and 2020 years that the term entered the mainstream, and made it almost exclusive on the west coast. This is because scientists were tracking and closely studying atmospheric rivers in universities there, with hundreds of research work that identify them as an important source of rain and snow and the great almost unique floods and Waxington. A remarkable example: a series of nine atmospheric rivers soaked California in December 2022 and January 2023, causing weeks of generalized floods and relieving a drought of years.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, known for his popular comment on meteorology, said the interest in atmospheric rivers generally increases the exceptionally humid and torments periods in California. He likes the label, but said that sometimes he is used and exaggerated, and that can lead to confusion around the severity of a storm. The media can deceive the public when they do not distinguish between unpleasant atmospheric rivers, the moderate ones that bring beneficial rains and the most substantial, even terrifying, that cause destruction, he said.

“The only real trap is this notion that all atmospheric rivers are really extreme and destructive events, because, of course, that is not true,” said Swain.

In 2019 a classification scale of atmospheric rivers was presented to help relieve this confusion. Dr. Marty Ralph, director of the Western Climate Center and water ends with the Oceanography Scripps institution in San Diego, directed the development of the west coast scale and has applied it in other areas of the world, including Antarctica and Antarctica. He has greatly promoted research, and marketing, of the term Atmospheric River, especially in California. He and his team have written papers boxes.

“It was Marty Ralph who organized the scientific community about this idea that atmospheric rivers are a phenomenon that is studying in Horth, and I think that prominence led people implicitly to the associated atmospheres that we had left the beginnings of omission, we would forgive the omission fields, we were WASE WON WER WERE WERE WER

That association, or lack of one, has dropped to daily forecasts, where the crimes of the west coast of the weather service will commonly discuss the atmospheric rivers, but the offices in other parts of the country do not.

“In general, we do not describe it that way in the west and southeast,” said Jimmy Barham, a main meteorologist of the Arkansas weather service. “We are only going to say the humidity of higher level.”

The emphasis on the West Coast has also meant that atmospheric rivers have been studied less in other parts of the country, where hurricanes and summer thunderstorms are also large rains and receive close attention.

Dr. Ralph hopes to see the investigation expand to the east coast.

“It turns out that the interior or a great Nor’ester often stalks a very strong atmospheric river, if not exceptionally strong,” he said, “and that has not traditionally recognized the legs, but the investigation is beginning to document that.”